Wild Strawberries (film)

| Wild Strawberries | |

|---|---|

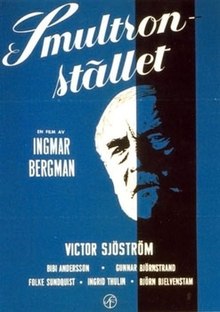

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Written by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Produced by | Allan Ekelund |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gunnar Fischer |

| Edited by | Oscar Rosander |

| Music by | Erik Nordgren |

| Distributed by | AB Svensk Filmindustri |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | Sweden |

| Language | Swedish |

Wild Strawberries is a 1957 Swedish drama film written and directed by Ingmar Bergman. The original Swedish title is Smultronstället, which literally means "the wild strawberry patch" but idiomatically signifies a hidden gem of a place, often with personal or sentimental value, and not widely known. The cast includes Victor Sjöström in his final screen performance as an old man recalling his past, as well as Bergman regulars Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, and Gunnar Björnstrand. Max von Sydow and Gunnel Lindblom also appear in small roles.

Bergman wrote the screenplay while hospitalized.[1] Exploring philosophical themes such as introspection and human existence, Wild Strawberries received wide positive domestic reception upon release, and won the Golden Bear for Best Film at the 8th Berlin International Film Festival. It is often considered to be one of Bergman's best films, as well as one of the greatest films ever made.[2]

Plot

[edit]Grouchy, stubborn, and egotistical Professor Isak Borg is a widowed 78-year-old physician who specialized in bacteriology. Before specializing, he served as a general practitioner in rural Sweden. He sets out on a long car ride from Stockholm to Lund to be awarded the degree of Doctor Jubilaris 50 years after he received his doctorate from Lund University. He is accompanied by his pregnant daughter-in-law Marianne who does not much like her father-in-law and is planning to separate from her husband, Evald, Isak's only son. Evald does not want her to have the baby, their first.

During the trip, Isak is forced by nightmares, daydreams, old age, and impending death to reevaluate his life. He meets a series of hitchhikers, each of whom sets off dreams or reveries into Borg's troubled past. The first group consists of two young men and their companion, a woman named Sara who is adored by both men. Sara is a double for the love of Isak's youth. He reminisces about his childhood at the seaside and his sweetheart Sara, with whom he remembered gathering strawberries, but who instead married his brother. The first group remains with him throughout his journey. Next Isak and Marianne pick up an embittered middle-aged couple, the Almans, whose vehicle had nearly collided with theirs. The pair exchanges such terrible vitriol and venom that Marianne stops the car and demands that they leave. The couple reminds Isak of his own unhappy marriage. In a dream sequence, Isak is asked by Sten Alman, now the examiner, to read "foreign" letters on the blackboard. He cannot. So, Alman reads it for him: "A doctor's first duty is to ask forgiveness," from which he concludes, "You are guilty of guilt."[3]

He is confronted by his loneliness and aloofness, recognizing these traits in both his elderly mother (whom they stop to visit) and in his middle-aged physician son, and he gradually begins to accept himself, his past, his present, and his approaching death.[4][5][6]

Borg finally arrives at his destination and is promoted to Doctor Jubilaris, but this proves to be an empty ritual. That night, he bids a loving goodbye to his young friends, to whom the once bitter old man whispers in response to a playful declaration of the young girl's love, "I'll remember." As he goes to his bed in his son's home, he is overcome by a sense of peace, and dreams of a family picnic by a lake. Closure and affirmation of life have finally come, and Borg's face radiates joy.

Cast

[edit]- Victor Sjöström as Professor Isak Borg

- Bibi Andersson as Sara (both: Isak's cousin/hitchhiker)

- Ingrid Thulin as Marianne Borg

- Gunnar Björnstrand as Evald Borg

- Jullan Kindahl as Agda, Isak's housekeeper

- Folke Sundquist as Anders, hitchhiker

- Björn Bjelfvenstam as Viktor, hitchhiker

- Naima Wifstrand as Isak's Mother

- Gunnel Broström as Berit Alman, angry wife

- Gunnar Sjöberg as Sten Alman, angry husband / The Examiner

- Max von Sydow as Henrik Åkerman, gas station attendant

- Ann-Marie Wiman as Eva Åkerman

- Gertrud Fridh as Karin Borg, Isak's wife

- Åke Fridell as Karin's lover

- Sif Ruud as Aunt Olga

- Yngve Nordwall as Uncle Aron

- Per Sjöstrand as Sigfrid Borg

- Gio Petré as Sigbritt Borg

- Gunnel Lindblom as Charlotta Borg

- Maud Hansson as Angelica Borg

- Eva Norée as Anna Borg

- Göran Lundquist as Benjamin Borg

- Per Skogsberg as Hagbart Borg

- Lena Bergman as Kristina Borg, twin

- Monica Ehrling as Birgitta Borg, twin

Production

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Bergman's idea for the film originated on a drive from Stockholm to Dalarna during which he stopped in Uppsala, his hometown. Driving by his grandmother's house, he suddenly imagined how it would be if he could open the door and inside find everything just as it was during his childhood. "So it struck me — what if you could make a film about this; that you just walk up in a realistic way and open a door, and then you walk into your childhood, and then you open another door and come back to reality, and then you make a turn around a street corner and arrive in some other period of your existence, and everything goes on, lives. That was actually the idea behind Wild Strawberries".[7][page needed] Later, he would revise the story of the film's genesis. In Images: My Life in Film, he comments on his own earlier statement: "That's a lie. The truth is that I am forever living in my childhood."[8]: p22

Development

[edit]Bergman wrote the screenplay of Wild Strawberries in Stockholm's Karolinska Hospital (the workplace of Isak Borg) in the late spring of 1957; he'd recently been given permission to proceed by producer Carl Anders Dymling on the basis of a short synopsis. He was in the hospital for two months, being treated for recurrent gastric problems and general stress. Bergman's doctor at Karolinska was his good friend Sture Helander who invited him to attend his lectures on psychosomatics. Helander was married to Gunnel Lindblom who was to play Isak's sister Charlotta in the film. Bergman was at a high point of his professional career after a triumphant season at the Malmö City Theatre (where he had been artistic director since 1952), in addition to the success of both Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) and The Seventh Seal (1957). His private life, however, was in disarray. His third marriage was on the rocks; his affair with Bibi Andersson, which had begun in 1954, was coming to an end; and his relationship with his parents was, after an attempted reconciliation with his mother, at a desperately low ebb.[8]: p17

Casting and pre-production progressed rapidly. The completed screenplay is dated 31 May. Shooting took place between 2 July 1957 and 27 August 1957.[9] The scenes at the summer house were filmed in Saltsjöbaden, a fashionable resort in the Stockholm archipelago. Part of the nightmare sequence was shot with predawn summer light in Gamla stan, the old part of central Stockholm. Most of the movie was made at SF's studio and on its back lot at Råsunda in northern Stockholm.[1]

Casting

[edit]The director's immediate choice for the leading role of the old professor was Victor Sjöström, Bergman's silent film idol and early counselor at Svensk Filmindustri, whom he had directed in To Joy eight years earlier. "Victor," Bergman remarked, "was feeling wretched and didn't want to [do it];... he must have been seventy eight. He was misanthropic and tired and felt old. I had to use all my powers of persuasion to get him to play the part."[10]

In Bergman on Bergman, he has stated that he only thought of Sjöström when the screenplay was complete, and that he asked Dymling to contact the famous actor and film director.[11] Yet in Images: My Life in Film, he claims, "It is probably worth noting that I never for a moment thought of Sjöström when I was writing the screenplay. The suggestion came from the film's producer, Carl Anders Dymling. As I recall, I thought long and hard before I agreed to let him have the part."[8]: p24

During the shooting, the health of the 78-year-old Sjöström gave cause for concern. Dymling had persuaded him to take on the role with the words: "All you have to do is lie under a tree, eat wild strawberries and think about your past, so it's nothing too arduous." This was inaccurate and the burden of the film was completely on Sjöström who is in all but one scene of the film. Initially, Sjöström had problems with his lines which made him frustrated and angry. He would go off into a corner and beat his head against the wall in frustration, even to the point of drawing blood and producing bruises. He sometimes quibbled over details in the script. To unburden his revered mentor, Bergman made a pact with Ingrid Thulin that if anything went wrong during a scene, she would take the blame on herself. Things improved when they changed filming times so that Sjöström could get home in time for his customary late afternoon whisky at 5:00. Sjöström got along particularly well with Bibi Andersson.[1]

As usual, Bergman chose his collaborators from a team of actors and technicians with whom he had worked before in the cinema and the theater. As Sara, Bibi Andersson plays both Borg's childhood sweetheart who left him to marry his brother and a charming, energetic young woman who reminds him of that lost love. Andersson, then twenty one years old, was a member in Bergman's famed repertory company. He gave her a small part in his films Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) and as the jester's wife in The Seventh Seal (1957). She would continue to work for him in many more films, most notably in Persona (1966). Ingrid Thulin plays Marianne, the sad, gentle and warm daughter-in-law of Borg. She appeared in other Bergman films as the mistress in Winter Light (1963) and as one of three sisters in Cries and Whispers (1972).

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]Wild Strawberries received strongly positive reviews in Sweden; its acting, script, and photography were common areas of praise.[12] It was among the films that cemented Bergman's international reputation,[13] but American critics were not unanimous in their praise. A number of reviewers found its story puzzling. In The New York Times, Bosley Crowther lauded the performances of Sjöström and Andersson but wrote, "This one is so thoroughly mystifying that we wonder whether Mr. Bergman himself knew what he was trying to say."[14] The film ranked 7th on Cahiers du Cinéma's Top 10 Films of the Year List in 1959.[15]

In a 1963 interview with Cinema magazine, director Stanley Kubrick listed the film as his second favourite of all time.[16] It was also listed by Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky as one of his top ten favorite films.[17] It is now considered one of Bergman's major works. Film critic Derek Malcolm ranked the film at No. 56 on his list of the "Top 100 Movies" in 2001.[18] In 2007, the film was ranked at No. 34 by The Guardian's readers poll on the list of "40 greatest foreign films of all time".[19] In 2009, the film was ranked at No. 59 on Japanese film magazine kinema Junpo's Top 100 Non-Japanese Films of All Time list.[20]

In 1972, the work was ranked 10th, in 2002 it was ranked 27th,[21] and in 2012, it ranked 63rd on the Sight & Sound critics' poll of the greatest films ever made.[22] That same year the film was voted at number 11 on the 25 best Swedish films of all time list by a poll of 50 film critics and academics conducted by film magazine FLM.[23] Its screenplay was listed in Total Film as one of the 50 best ever written.[24] The film was included in BBC's 2018 list of The 100 greatest foreign language films.[25] In 2022 edition of Sight & Sound's Greatest films of all time list the film ranked 72nd in the director's poll.[26]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Wild Strawberries has an approval rating of 96% based on 45 reviews, with an average score of 8.90/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Wild Strawberries were never so bittersweet as Ingmar Bergman's beautifully written and filmed look at one man's nostalgic journey into the past."[27] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 88 out of 100 based on 17 critic's reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[28]

The philosopher Roger Scruton wrote of the film: "Even now, after ten viewings, I want to see Wild Strawberries again, not for the story only, but for specific snatches of dialogue, specific images and the specific atmosphere which makes this film enter the soul with the evocative force of a play by Ibsen or Strindberg."[29]

Awards and honors

[edit]The film won the Golden Bear for Best Film and the FIPRESCI Prize[30] at the 8th Berlin International Film Festival,[31] "Best Film" and "Best Actor" at the Mar del Plata Film Festival and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Film in 1960. The Film was nominated for a BAFTA Award in Best Film From Any Source category in 1959. It was also nominated for an Academy Award for Original Screenplay, but the nomination was refused by Bergman.[32] In his letter to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Bergman wrote, "I have found that the "Oscar" nomination is one for the motion picture art humiliating institution and ask you to be released from the attention of the jury for the future."[33] The film won the Pasinetti Award at 1958 Venice Film Festival. It won the Bodil Award for Best European Film in 1959.[34]

The film is included on the Vatican's list of important films, recommended for its portrayal of a man's "interior journey from pangs of regret and anxiety to a refreshing sense of peace and reconciliation".[35]

Influence

[edit]Wild Strawberries influenced the Woody Allen films Stardust Memories (1980), Another Woman (1988), Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), and Deconstructing Harry (1997). In Stardust Memories, the film's plot is similar in that the protagonist, filmmaker Sandy Bates (Woody Allen), is attending a viewing of his films, while reminiscing about and reflecting on his life and past relationships and trying to fix and stabilize his current ones, which are infused with flashbacks and dream sequences. In Another Woman, the film's main character, Marion Post (Gena Rowlands), is also accused by friends and relatives of being cold and unfeeling, which forces her to reexamine her life.[36] Allen also borrows several tropes from Bergman's film, such as having Lynn (Frances Conroy), Post's sister-in-law, tell her that her brother Paul (Harris Yulin) hates her and having a former student tell Post that her class changed her life. Allen has Post confront the demons of her past via several dream sequences and flashbacks that reveal important information to a viewer, as in Wild Strawberries. In Crimes and Misdemeanors, Allen made reference to the scene in which Isak watches his family have dinner.[37] In Deconstructing Harry, the plot (a writer going on a long drive to receive an honorary award from his old university, while reflecting upon his life's experiences, with dream sequences) essentially mirrors that of Wild Strawberries.[38]

Satyajit Ray's 1966 film Nayak was to some extent inspired by Wild Strawberries.[39]

Yugoslav hard rock and heavy metal band Divlje Jagode (Serbo-Croatian for Wild Strawberries) chose their name after the film.[40] During their short-lived international career, the band adopted the name Wild Strawberries.[41]

Attempted American remake

[edit]Screenwriter Bo Goldman sought to remake the film in 1995 as his directorial debut. Gregory Peck would have starred in the titular role of the elderly professor.[42] Despite the support of Martin Scorsese, who agreed to produce, the film was not green lit.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Wild Strawberries". The Ingmar Bergman Foundation. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ Murray, Edward (1978). Ten Film Classics: A Re-viewing. F. Ungar Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8044-2650-3.

- ^ Erik Erikson "Wild Strawberries".

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (10 June 1999). "Ingmar Bergman: Wild Strawberries". The Guardian.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (23 June 1959). "Wild Strawberries (1957) NYT Critics' Pick". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ Manvell, Roger. "Plot and review: SMULTRONSTÄLLET (Wild Stawberries)". filmreference.com.

- ^ Björkman

- ^ a b c Bergman, Ingmar (1990). Images: my life in film. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 9781559701860.

- ^ "Smultronstället (1957) - Filming Locations". Swedish Film Institute (in Swedish).

- ^ Björkman, Stig (1973). Bergman on Bergman. Simon and Schuster. p. 133.

- ^ Björkman, pg. 131

- ^ Steene, Birgitta (2005). Ingmar Bergman: A Reference Guide. Amsterdam University Press. p. 231. ISBN 9053564063.

- ^ Nixon, Rob. "Wild Strawberries". Turner Classic Movies, Inc. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (23 June 1959). "Screen: Elusive Message; Wild Strawberries' Is a Swedish Import". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2017. Crowther also notes "the English subtitles are not much help", so some confusion was created by poor subtitles in the 1959 screening. To take just one example, in the review he states that it's unclear if the main character was a physician or a doctor, whereas in the script this is eminently clear, in fact an important scene is when the traveling party stops to refuel and the gas attendant refuses to take payment for the gasoline and extols all the good that the "good doctor" has done for the community, to which the old man replies mostly to himself "maybe I should have stayed".

- ^ Johnson, Eric C. "Cahiers du Cinema: Top Ten Lists 1951-2009". alumnus.caltech.edu. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Ciment, Michel (1982). "Kubrick: Biographical Notes". The Kubrick Site. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ Lasica, Tom. "Tarkovsky's Choice". Nostalghia.com. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (18 January 2001). "Derek Malcolm's top 100 movies". The Guardian.

- ^ "As chosen by you...the greatest foreign films of all time". The Guardian. 11 May 2007.

- ^ "「オールタイム・ベスト 映画遺産200」全ランキング公開". Kinema Junpo. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010.

- ^ "The Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 The Rest of Critic's List". old.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 June 2012.

- ^ "'Wild Strawberries' (1957)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012.

- ^ "De 25 bästa svenska filmerna genom tiderna". Flm (in Swedish). 30 August 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Kinnear, Simon (30 September 2013). "50 Best Movie Screenplays". Total Film. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Foreign Language Films". bbc. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Directors' 100 Greatest Films of All Time". bfi.org.

- ^ "Wild Strawberries". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "Wild Strawberries". Metacritic.

- ^ "Ingmar Bergman: the sense of the world". opendemocracy.net.

- ^ "Ingmar Bergman". fipresci.

- ^ "PRIZES & HONOURS 1958". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Soares, Andre. "Ingmar Bergman vs. the Oscar". Alt Film Guide. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Bose, Swapnil Dhruv (10 September 2023). "Why did Ingmar Bergman reject his Oscar nomination?". Far Out. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "Denmark's National Union of Film Critics". bodilprisen.

- ^ "Vatican Best Films List". U.S. Catholic Bishops — Office of Film and Broadcasting. Archived from the original on 23 November 2001.

- ^ "Another Woman". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Fraley, Jason. "Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989) | The Film Spectrum". Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Deconstructing Harry". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ "NAYAK vs WILD STRAWBERRIES | Inspiration Behind Satyajit Ray's masterpiece | Uttam Kumar | Bergman". YouTube. 5 July 2020.

- ^ Janjatović, Petar (2024). Ex YU rock enciklopedija 1960–2023. Belgrade: self-released / Makart. p. 86.

- ^ Janjatović, Petar (2024). Ex YU rock enciklopedija 1960–2023. Belgrade: self-released / Makart. p. 87.

- ^ "FORD TO STAR IN 'SABRINA' AFTER TAKING YEAR OFF". Orlando Sentinel. 10 February 1995. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

External links

[edit]- Wild Strawberries at IMDb

- Wild Strawberries at the Swedish Film Institute Database

- Wild Strawberries at the TCM Movie Database

- Wild Strawberries at Rotten Tomatoes

- Wild Strawberries an essay by Peter Cowie at the Criterion Collection

- 1957 films

- 1957 drama films

- Swedish black-and-white films

- Existentialist films

- Films about old age

- Films directed by Ingmar Bergman

- Films shot in Sweden

- Films set in the 1890s

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films set in Sweden

- Films with screenplays by Ingmar Bergman

- Golden Bear winners

- 1950s drama road movies

- Swedish drama films

- 1950s Swedish-language films

- Philosophical fiction

- Films scored by Erik Nordgren

- Films about dreams

- 1950s Swedish films