Philadelphia chromosome

| Philadelphia chromosome | |

|---|---|

| |

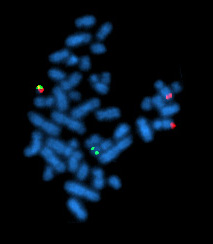

| A metaphase cell positive for the bcr/abl rearrangement using FISH | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

The Philadelphia chromosome or Philadelphia translocation (Ph) is an abnormal version of chromosome 22 where a part of the Abelson murine leukemia 1 (ABL1) gene on chromosome 9 breaks off and attaches to the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene in chromosome 22[1][2]. The balanced reciprocal translocation between the long arms of 9 and 22 chromosomes [t (9; 22) (q34; q11)] results in the fusion gene BCR::ABL1[2]. The oncogenic protein with persistently enhanced tyrosine kinase activity transcribed by the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene can lead to rapid, uncontrolled growth of immature white blood cells that accumulates in the blood and bone marrow[3][1].

The Philadelphia chromosome is present in the bone marrow cells of a vast majority chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) patients. The expression patterns off different BCR-ABL1 transcripts vary during the progression of CML. Each variant is present in a distinct leukemia phenotype and can be used to predict response to therapy and clinical outcomes. The Ph is also observed in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), and mixed-phenotype acute leukemia[1][3].

Molecular biology

[edit]

The chromosomal defect in the Philadelphia chromosome is a reciprocal translocation, in which parts of two chromosomes, 9 and 22, swap places. The result is that a fusion gene is created by juxtaposing the ABL1 gene on chromosome 9 (region q34) to a part of the BCR (breakpoint cluster region) gene on chromosome 22 (region q11). This is a reciprocal translocation, creating an elongated chromosome 9 (termed a derivative chromosome, or der 9), and a truncated chromosome 22 (the Philadelphia chromosome, 22q-).[4][5] In agreement with the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN), this chromosomal translocation is designated as t(9;22)(q34;q11). The symbol ABL1 is derived from Abelson, the name of a leukemia virus which carries a similar protein. The symbol BCR is derived from breakpoint cluster region, a gene which encodes a protein that acts as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rho GTPase proteins.[6]

Translocation results in an oncogenic BCR::ABL1 gene fusion that can be found on the shorter derivative chromosome 22. This gene encodes for a BCR::ABL1 fusion protein. Depending on the precise location of fusion, the molecular weight of this protein can range from 185 to 210 kDa. Consequently, the hybrid BCR::ABL1 fusion protein is referred to as p210 or p185.

Three clinically important variants encoded by the fusion gene are the p190, p210, and p230 isoforms.[7] p190 is generally associated with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), while p210 is generally associated with chronic myeloid leukemia but can also be associated with ALL and AML.[8] p230 is usually associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia associated with neutrophilia and thrombocytosis (CML-N).[8] Additionally, the p190 isoform can also be expressed as a splice variant of p210.[9]

The ABL1 gene expresses a membrane-associated protein, a tyrosine kinase, and the BCR::ABL1 transcript is also translated into a tyrosine kinase containing domains from both the BCR and ABL1 genes. The activity of tyrosine kinases is typically regulated in an auto-inhibitory fashion, but the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene codes for a protein that is "always on" or constitutively activated, leading to impaired DNA binding and unregulated cell division (i.e. cancer). This is due to the replacement of the myristoylated cap region, which when present induces a conformational change rendering the kinase domain inactive, with a truncated portion of the BCR protein.[10] Although the BCR region also expresses serine/threonine kinases, the tyrosine kinase function is very relevant for drug therapy. As the N-terminal Y177 and CC domains from BCR encode the constitutive activation of the ABL1 kinase, these regions are targeted in therapies to downregulate BCR::ABL1 kinase activity. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors specific to such domains as CC, Y177, and Rho (such as imatinib and sunitinib) are important drugs against a variety of cancers including CML, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).

The fused BCR::ABL1 protein interacts with the interleukin-3 receptor beta(c) subunit and is moderated by an activation loop within its SH1 domain, which is turned "on" when bound to ATP and triggers downstream pathways. The ABL1 tyrosine kinase activity of BCR::ABL1 is elevated relative to wild-type ABL1.[11] Since ABL activates a number of cell cycle-controlling proteins and enzymes, the result of the BCR::ABL1 fusion is to speed up cell division. Moreover, it inhibits DNA repair, causing genomic instability and potentially causing the feared blast crisis in CML.

Proliferative roles in leukemia

[edit]The BCR::ABL1 fusion gene and protein encoded by the Philadelphia chromosome affects multiple signaling pathways that directly affect apoptotic potential, cell division rates, and different stages of the cell cycle to achieve unchecked proliferation characteristic of CML and ALL.

JAK/STAT pathway

[edit]Particularly vital to the survival and proliferation of myelogenous leukemia cells in the microenvironment of the bone marrow is cytokine and growth factor signaling. The JAK/STAT pathway moderates many of these effectors by activating STATs, which are transcription factors with the ability to modulate cytokine receptors and growth factors. JAK2 phosphorylates the BCR::ABL1 fusion protein at Y177 and stabilizes the fusion protein, strengthening tumorigenic cell signaling. JAK2 mutations have been shown to be central to myeloproliferative neoplasms and JAK kinases play a central role in driving hematologic malignancies (JAK blood journal). ALL and CML therapies have targeted JAK2 as well as BCR::ABL1 using nilotinib and ruxolitinib within murine models to downregulate downstream cytokine signaling by silencing STAT3 and STAT5 transcription activation (appelmann et al.). The interaction between JAK2 and BCR::ABL1 within these hematopoietic malignancies implies an important role of JAK-STAT-mediated cytokine signaling in promoting the growth of leukemic cells exhibiting the Ph chromosome and BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase activity. Though the centrality of the JAK2 pathway to direct proliferation in CML has been debated, its role as a downstream effector of the BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase has been maintained. Impacts on the cell cycle via JAK-STAT are largely peripheral, but by directly impacting the maintenance of the hematopoietic niche and its surrounding microenvironment, the BCR::ABL1 upregulation of JAK-STAT signaling plays an important role in maintaining leukemic cell growth and division.[12][13]

Ras/MAPK/ERK pathway

[edit]The Ras/MAPK/ERK pathway relays signals to nuclear transcription factors and plays a role in governing cell cycle control and differentiation. In Ph chromosome-containing cells, the BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase activates the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, which results in unregulated cell proliferation via gene transcription in the nucleus. The BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase activates Ras via phosphorylation of the GAB2 protein, which is dependent on BCR-located phosphorylation of Y177. Ras in particular is shown to be an important downstream target of BCR::ABL1 in CML, as Ras mutants in murine models disrupt the development of CML associated with the BCR::ABL1 gene (Effect of Ras inhibition in hematopoiesis and BCR::ABL1 leukemogenesis). The Ras/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway is also implicated in overexpression of osteopontin (OPN), which is important for maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell niche, which indirectly influences unchecked proliferation characteristic of leukemic cells.[14] BCR::ABL1 fusion cells also exhibit constitutively high levels of activated Ras bound to GTP, activating a Ras-dependent signaling pathway which has been shown to inhibit apoptosis downstream of BCR::ABL1 (Cortez et al.). Interactions with the IL-3 receptor also induce the Ras/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway to phosphorylate transcription factors which play a role in driving the G1/S transition of the cell cycle.[15][16][17]

DNA binding and apoptosis

[edit]The c-Abl gene in wild-type cells is implicated in DNA binding, which affects such processes as DNA transcription, repair, apoptosis, and other processes underlying the cell cycle. While the nature of this interaction has been debated, evidence exists to suggest that c-Abl phosphorylates HIPK2, a serine/threonine kinase, in response to DNA damage and promotes apoptosis in normal cells. The BCR::ABL1 fusion, in contrast, has been shown to inhibit apoptosis, but its effect on DNA binding in particular is unclear.[18] In apoptotic inhibition, BCR::ABL1 cells have been shown to be resistant to drug-induced apoptosis but also have a proapoptotic expression profile by increased expression levels of p53, p21, and Bax. The function of these pro-apoptotic proteins, however, is impaired, and apoptosis is not carried out in these cells. BCR::ABL1 has also been implicated in preventing caspase 9 and caspase 3 processing, which adds to the inhibitory effect.[19][20] Another factor preventing cell cycle progression and apoptosis is the deletion of the IKAROS gene, which presents in >80% of Ph chromosome–positive ALL cases. The IKAROS gene is critical to pre-B cell receptor–mediated cell cycle arrest in ALL cells positive for Ph, which when impaired provides a mechanism for unchecked cell cycle progression and proliferation of defective cells as encouraged by BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase signaling.[21]

Nomenclature

[edit]| Nomenclature | Definition |

| BCR | Breakpoint Cluster Region |

| ABL1 | Abelson Tyrosine Kinase 1 |

| Ph+ | Philadelphia chromosome positive |

| Ph-like | Similar gene expression profile to Ph+ |

| t(9;22)(q34;q11) | |

| t | translocation |

| (9;22) | exchange between chromosomes 9 and 22 |

| q34 | ABL1 gene on chromosome 9 |

| q11.2 | BCR gene on chromosome 22 |

Table 1. Philadelphia chromosome nomenclature defined by the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, from a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 t(9;22)(q34;q11)[22][23][24].

| Ph Type | Protein Size | Disease Association |

| P210 BCR-ABL1 | 210 kDa | Classical CML, Ph+ ALL (~30%) |

| P190 BCR-ABL1 | 190 kDa | Ph+ ALL (~70%), rare in CML |

| P230 BCR-ABL1 | 230 kDa | Chronic Neutrophilic Leukemia (CNL), rare CML variant |

Table 2. The size and disease association of the different BCR-ABL1 fusion proteins based on the breakpoints in the BCR and ABL1 genes[24].

Therapy

[edit]The primary objective of Ph+ CML and ALL treatment is to improve survival rates to match the general population. A secondary objective, although achieved in fewer patients, is a deep molecular response (DMR), which can allow treatment discontinuation and lead to a treatment-free remission[25].

The main treatment options for Ph+ leukemias are Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), chemotherapy, often in combination with TKIs, and allogeneic treatments such as stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Chemotherapy is often used before stem cell transplantation in high-risk patients. HSCT is used for younger or high-risk patients who don’t respond well to TKIs[25][26].

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

[edit]

The BCR-ABL fusion gene produces an abnormal tyrosine kinase that drives Ph+ leukemia. TKIs target the BRC-ABL1 fusion protein and block the abnormal tyrosine kinase activity, preventing uncontrolled cell proliferation[28]. The first TKI was approved in the US in 2001, since 5 additional BCR::ABL1 TKIs have been approved by the US food and drug administration (FDA)[29]. The TKIs are categorized in generations pertaining to potency, whereas each subsequent generation is effective to mutations with resistance to the previous generation[25][29].

| BCR::ABL1 TKI | Generation |

| Imatinib | First-generation |

| Dasatinib, Nilotinib, Bosutinib | Second-generation |

| Ponatinib, Asciminib | Third-generation |

Table 3. FDA approved BCR::ABL1 TKIs categorized by generation[29].

The introduction of TKIs was initially alongside chemotherapy. Prior to TKIs, chemotherapy had been the standard treatment for Ph-positive leukemia with limited success and low, long-term survival rates[29]. The combination improved survival rates resulted in more patients achieving hematologic remission, where leukemia cells can no longer be detected in the blood. However, this approach had significant side effects, with some patients dying from complications during early phases of treatment[26]. Further research explored the use of TKIs with reduced-intensity chemotherapy and since 2004, clinical trials in Italy have used TKIs without chemotherapy during the first phase of treatment. This approach led to higher remission rates, fewer complications and eligibility for elderly patients unable to tolerate intense chemotherapy[26].

Allogeneic transplantation and immunotherapy

[edit]Based on the patient’s condition and response to TKIs, other treatment options such as Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) or immunotherapy. HSCT is primarily considered for younger patients or high-risk patients that do not respond well to TKIs. The process involves transplanting bone marrow stem cells from a matched donor and is infrequently used to treat CML due to long-term complications and risk factors[26][29]. Traditionally Allogeneic transplantation has been the standard curative treatment for Ph+ leukemia however, studies suggest it may not improve survival in patients without minimal residual disease (MRD). Immunotherapies are often considered in MRD cases or in instances of relapsed patients. Third generation, more potent TKIs and immunotherapies, may lead to fewer patients requiring transplantation as standard treatment. For patients with persistent MRD, TKI resistant mutations or multiple relapses, HSCT should be considered[26]. Depending on the stage of CML, cure rates with HSCT range from 20% to 60%. Improved techniques have reduced relapse free mortality rates after transplant to ~12% after 5 years and has made HSCT feasible for older patients [29]. Post-transplant, TKI maintenance therapy is recommended[26].

Prognosis

[edit]The introduction of BCR::ABL1 targeting TKIs significantly improved Ph+ CML prognosis. TKIs have increased the 10-year overall survival rate from less than 20% to 80%-85%. This has resulted in a similar 10-year relative survival rate for patients with CML and age-matched CML negative controls[30].

History

[edit]In 1960, the Philadelphia chromosome was co-discovered by cytogeneticists David Hungerford and Peter Nowell[31][32]. The at the time junior faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Peter Nowell, through an accident managed to clearly see metaphase spreads in leukemic cells. This led him to seek the assistance of graduate student David Hungerford. Together they described an unusual, small chromosome present in leukocytes from patients with CML[33][34]. This finding provided strong evidence supporting Boveri’s hypothesis that a single genetic alteration could drive cancer development. While no other consistent chromosomal abnormalities were initially found in leukemias, the discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome marked a breakthrough in understanding cancer genetics[35].

The mechanism for which the Philadelphia chromosome arises as a translocation, not a deletion was discovered by Janet Rowley in 1972, and subsequent paper was published in 1973. Rowley used Giemsa staining and quinacrine banding to show that the Ph chromosome resulted from a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22. The presence of the t(9;22) translocation in nearly all bone marrow cells from CML patients implied that the abnormality was involved as a cause and not a result of the cancer[33][34].

In 1984, Nora Heisterkamp and John Groffen later mapped the breakpoints on chromosomes 9 and 22, identifying the BCR on chromosome 22 and its fusion with the ABL gene from chromosome 9[36]. Owen Witte’s work demonstrated that the abnormal tyrosine kinase produced by BRC-ABL fusion gene had enhanced kinase activity. Experiments introducing the BCR-ABL gene in mice led to CML-like disease, proving its central role in leukemia development[33].

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sampaio, Mariana Miranda; Santos, Maria Luísa Cordeiro; Marques, Hanna Santos; Gonçalves, Vinícius Lima de Souza; Araújo, Glauber Rocha Lima; Lopes, Luana Weber; Apolonio, Jonathan Santos; Silva, Camilo Santana; Santos, Luana Kauany de Sá; Cuzzuol, Beatriz Rocha; Guimarães, Quézia Estéfani Silva; Santos, Mariana Novaes; de Brito, Breno Bittencourt; da Silva, Filipe Antônio França; Oliveira, Márcio Vasconcelos (2021-02-24). "Chronic myeloid leukemia-from the Philadelphia chromosome to specific target drugs: A literature review". World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 12 (2): 69–94. doi:10.5306/wjco.v12.i2.69. ISSN 2218-4333. PMC 7918527. PMID 33680875.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/philadelphia-chromosome". www.cancer.gov. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2025-03-26.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b Kang, Zhi-Jie; Liu, Yu-Fei; Xu, Ling-Zhi; Long, Zi-Jie; Huang, Dan; Yang, Ya; Liu, Bing; Feng, Jiu-Xing; Pan, Yu-Jia; Yan, Jin-Song; Liu, Quentin (2016-12). "The Philadelphia chromosome in leukemogenesis". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 35 (1). doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0108-0. ISSN 1944-446X. PMC 4896164. PMID 27233483.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM, Druker BJ, Talpaz M (May 2003). "Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias: from basic mechanisms to molecular therapeutics". Annals of Internal Medicine. 138 (10): 819–830. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00010. PMID 12755554. S2CID 25865321.

- ^ Melo JV (May 1996). "The molecular biology of chronic myeloid leukaemia". Leukemia. 10 (5): 751–756. PMID 8656667.

- ^ "Gene entry for BCR". NCBI Gene. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Advani AS, Pendergast AM (August 2002). "Bcr-Abl variants: biological and clinical aspects". Leukemia Research. 26 (8): 713–720. doi:10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00197-7. PMID 12191565.

- ^ a b Pakakasama S, Kajanachumpol S, Kanjanapongkul S, Sirachainan N, Meekaewkunchorn A, Ningsanond V, Hongeng S (August 2008). "Simple multiplex RT-PCR for identifying common fusion transcripts in childhood acute leukemia". International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 30 (4): 286–291. doi:10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00954.x. PMID 18665825.

- ^ Lichty BD, Keating A, Callum J, Yee K, Croxford R, Corpus G, et al. (December 1998). "Expression of p210 and p190 BCR-ABL due to alternative splicing in chronic myelogenous leukaemia". British Journal of Haematology. 103 (3): 711–715. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01033.x. PMID 9858221.

- ^ Nagar B, Hantschel O, Young MA, Scheffzek K, Veach D, Bornmann W, et al. (March 2003). "Structural basis for the autoinhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase". Cell. 112 (6): 859–871. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00194-6. PMID 12654251.

- ^ Sattler M, Griffin JD (April 2001). "Mechanisms of transformation by the BCR/ABL oncogene". International Journal of Hematology. 73 (3): 278–291. doi:10.1007/BF02981952. PMID 11345193. S2CID 20999134.

- ^ Warsch W, Walz C, Sexl V (September 2013). "JAK of all trades: JAK2-STAT5 as novel therapeutic targets in BCR-ABL1+ chronic myeloid leukemia". Blood. 122 (13): 2167–2175. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-04-567289. PMID 23926299.

- ^ Hantschel O (February 2015). "Targeting BCR-ABL and JAK2 in Ph+ ALL". Blood. 125 (9): 1362–1363. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-12-617548. PMID 25721043.

- ^ Haylock DN, Nilsson SK (September 2006). "Osteopontin: a bridge between bone and blood". British Journal of Haematology. 134 (5): 467–474. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06218.x. PMID 16848793.

- ^ Bandyopadhyay G, Biswas T, Roy KC, Mandal S, Mandal C, Pal BC, et al. (October 2004). "Chlorogenic acid inhibits Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase and triggers p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemic cells". Blood. 104 (8): 2514–2522. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-11-4065. PMID 15226183.

- ^ Skorski T, Kanakaraj P, Ku DH, Nieborowska-Skorska M, Canaani E, Zon G, et al. (June 1994). "Negative regulation of p120GAP GTPase promoting activity by p210bcr/abl: implication for RAS-dependent Philadelphia chromosome positive cell growth". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 179 (6): 1855–1865. doi:10.1084/jem.179.6.1855. PMC 2191514. PMID 8195713.

- ^ Steelman LS, Pohnert SC, Shelton JG, Franklin RA, Bertrand FE, McCubrey JA (February 2004). "JAK/STAT, Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/Akt and BCR-ABL in cell cycle progression and leukemogenesis". Leukemia. 18 (2): 189–218. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403241. PMID 14737178.

- ^ Burke BA, Carroll M (June 2010). "BCR-ABL: a multi-faceted promoter of DNA mutation in chronic myelogeneous leukemia". Leukemia. 24 (6): 1105–1112. doi:10.1038/leu.2010.67. PMC 4425294. PMID 20445577.

- ^ "The Tyrosine Kinase c-Abl Responds to DNA Damage by Activating the Homeodomain-interacting Protein Kinase 2". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (27): 16489. 2015. doi:10.1074/jbc.p114.628982. PMC 4505403.

- ^ Kipreos ET, Wang JY (April 1992). "Cell cycle-regulated binding of c-Abl tyrosine kinase to DNA". Science. 256 (5055): 382–385. Bibcode:1992Sci...256..382K. doi:10.1126/science.256.5055.382. PMID 1566087. S2CID 29228735.

- ^ Qazi S, Uckun FM (December 2013). "Incidence and biological significance of IKZF1/Ikaros gene deletions in pediatric Philadelphia chromosome negative and Philadelphia chromosome positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Haematologica. 98 (12): e151 – e152. doi:10.3324/haematol.2013.091140. PMC 3856976. PMID 24323986.

- ^ Aboul-Soud, Mourad A. M.; Alzahrani, Alhussain J.; Mahmoud, Amer (2021-01-01). "Decoding variants in drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in solid tumor patients by whole-exome sequencing". Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 28 (1): 628–634. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.10.052. ISSN 1319-562X. PMC 7783809. PMID 33424349.

- ^ Kang, Zhi-Jie; Liu, Yu-Fei; Xu, Ling-Zhi; Long, Zi-Jie; Huang, Dan; Yang, Ya; Liu, Bing; Feng, Jiu-Xing; Pan, Yu-Jia; Yan, Jin-Song; Liu, Quentin (2016-05-27). "The Philadelphia chromosome in leukemogenesis". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 35 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0108-0. ISSN 1944-446X. PMC 4896164. PMID 27233483.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Sattler, Martin; Griffin, James D. (2001-04-01). "Mechanisms of Transformation by the BCR/ABL Oncogene". International Journal of Hematology. 73 (3): 278–291. doi:10.1007/BF02981952. ISSN 1865-3774.

- ^ a b c Senapati, Jayastu; Sasaki, Koji; Issa, Ghayas C.; Lipton, Jeffrey H.; Radich, Jerald P.; Jabbour, Elias; Kantarjian, Hagop M. (2023-04-24). "Management of chronic myeloid leukemia in 2023 – common ground and common sense". Blood Cancer Journal. 13 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1038/s41408-023-00823-9. ISSN 2044-5385. PMC 10123066. PMID 37088793.

- ^ a b c d e f Foà, Robin; Chiaretti, Sabina (2022-06-22). "Philadelphia Chromosome–Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". New England Journal of Medicine. 386 (25): 2399–2411. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2113347. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ^ Panjarian, Shoghag; Iacob, Roxana E.; Chen, Shugui; Engen, John R.; Smithgall, Thomas E. (2013-02-22). "Structure and Dynamic Regulation of Abl Kinases*". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (8): 5443–5450. doi:10.1074/jbc.R112.438382. ISSN 0021-9258. PMC 3581414. PMID 23316053.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Komorowski, Lukasz; Fidyt, Klaudyna; Patkowska, Elżbieta; Firczuk, Malgorzata (2020-08-12). "Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Leukemia in the Lymphoid Lineage—Similarities and Differences with the Myeloid Lineage and Specific Vulnerabilities". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (16): 5776. doi:10.3390/ijms21165776. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 7460962. PMID 32806528.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f Jabbour, Elias; Kantarjian, Hagop (2025-03-17). "Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Review". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.0220. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ Jabbour, Elias; Kantarjian, Hagop (2025-03-17). "Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Review". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.0220. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ Ortiz-Hidalgo, Carlos (2025-03-19). "History of Leukemia, Revisited". Current Oncology Reports. doi:10.1007/s11912-025-01658-2. ISSN 1534-6269.

- ^ Rudkin, George T.; Hungerford, David A.; Nowell, Peter C. (1964-06-05). "DNA Contents of Chromosome Ph1 and Chromosome 21 in Human Chronic Granulocytic Leukemia". Science. 144 (3623): 1229–1232. doi:10.1126/science.144.3623.1229.

- ^ a b c Chandra, H. Sharat; Heisterkamp, Nora C.; Hungerford, Alice; Morrissette, Jennifer J. D.; Nowell, Peter C.; Rowley, Janet D.; Testa, Joseph R. (2011-04-01). "Philadelphia Chromosome Symposium: commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the Ph chromosome". Cancer Genetics. 204 (4): 171–179. doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2011.03.002. ISSN 2210-7762. PMC 3092778. PMID 21536234.

- ^ a b Koretzky, Gary A. (2007-08-01). "The legacy of the Philadelphia chromosome". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (8): 2030–2032. doi:10.1172/JCI33032. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 1934583. PMID 17671635.

- ^ Nowell, Peter C. (2007-08-01). "Discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome: a personal perspective". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (8): 2033–2035. doi:10.1172/JCI31771. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 1934591. PMID 17671636.

- ^ Groffen, John; Stephenson, John R.; Heisterkamp, Nora; Klein, Annelies de; Bartram, Claus R.; Grosveld, Gerard (1984-01-01). "Philadelphia chromosomal breakpoints are clustered within a limited region, bcr, on chromosome 22". Cell. 36 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90077-1. ISSN 0092-8674.

External links

[edit]- Philadelphia+chromosome at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- bcr-abl+Fusion+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)